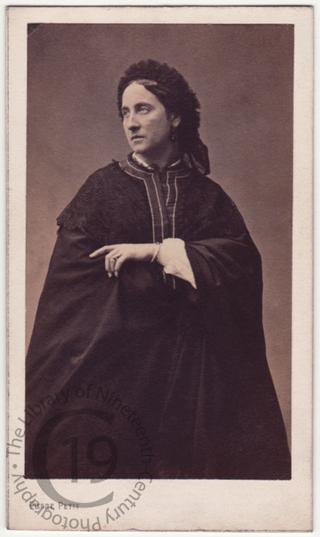

Adelaide Ristori

The French theatre of the mid-nineteenth century was dominated by two great actresses with very different acting styles, Rachel and Ristori, and a fierce partisanship arose between their supporters. When Ristori first appeared, in André Maffei's translation of Schiller's Maria Stuarda, French audiences were struck by the contrast between her fiery Latin style of gesticulation compared with the controlled, restrained, introverted technique that Rachel had popularised since her debut in 1838 at the age of seventeen.

Critics were divided in their reception of Ristori's style. Jules Lecomte charged that Adelaide Ristori 'often offers a disagreeably drawn pantomime, vulgar attitudes...The exaggeration of her acting, the affectation of her delivery, her unbearable sing-song, her often vulgar gestures, and her face contracted to the point of ugliness place her among the boulevard celebrities.'

However, this same variety and exaggeration of expression prompted Alexandre Dumas to write that 'the prodigious tragedienne, in the course of two hours, was at once tender, awful, calm, ardent, loving, jealous, menacing, despairing.' The seeming spontaneity and range of her emotional display impressed another critic, who wrote: 'Everything in her gushes forth - vocal intonation, gesture, gaze, facial expression, - without [the audience] ever once sensing effort, calculation or preparation.'

Public disenchantment with Rachel was further fuelled the following year when the actress stayed away from Paris to nurse her dying sister and was sued for breach of contract by the playwright Ernest Legouvé, who had created his Medea especially for her. In 1856 the play opened with Ristori in the lead.

The rivalry between Ristori and Rachel of 1855 and 1856 may have begun with debates over the style of their theatrical performances, but it soon became an excuse for artists and writers to discuss the relationship of the contemporary to the ancient, and the modern to the classical. Rachel, as an established figure, became a symbol of all that was traditional, restrained, and controlled within the social system. Her overthrow was seen as almost as profound a redefinition of classical values as the 1848 coup d'état had been in the political world.

Photographed by Pierre Petit of Paris.

Code: 124464